The Neuroscience of Teenage Career Decision Making

30/10/19

Russell Booth is a qualified and experienced career practitioner with 20 years experience both in New Zealand and England. Russell is a Fellow Member of CDANZ (Career Development Association of New Zealand) and also a past-president of CDANZ. He has a Secondary Teaching qualification, a Masters in Education and a Post Grad Diploma in Business.

I have recently started asking young people how they feel about the question, ‘what do you want to do when you leave school?’ It is very clear they really dislike the question; some say they hate it and most dread being asked the question. They also know that the closer they get to the end of their school years and the end of school exams the more they will get asked the question.

The reason they give the answers they do is that the question brings to the surface a lot of confusion, uncertainty and anxiety. They know the question is not about what they are going to do immediately after school but what are they going to do in life – for a career.

They say that they often don’t have a stable and constant picture about what they want to do. It changes often and quite quickly, which confuses them, and they find this hard to explain to people. So, their answers are vague because that is exactly how they feel.

So about 3 years ago, I realised that the development of the adolescent brain may have a role in this anxiety and uncertainty in making career decisions. Having read many scientific papers and books on the adolescent brain and spoken to as many knowledgeable people on the subject I could, this is what I have found out.

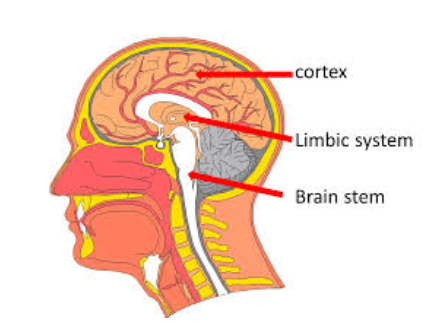

Scientists have recently learned a great deal about two main areas of the young developing brain:

- The prefrontal cortex, which in effect is the CEO of the brain, and the

- limbic system, which is the emotional engine-room.

What they know is that from adolescence (puberty to about 18), through emerging or young adulthood (about 18 to around 25) and into later adulthood (from mid-20s onwards), the prefrontal cortex undergoes significant neurological changes and starts to communicate better with and exert more control over the limbic brain. Slowly over this time, our brain starts to function more effectively and efficiently. We become more adult and more rational.

But there are no obvious tell-tale signs and actually being rational and adult is more a case of now you see it and now you don’t.

The prefrontal cortex houses the important executive function skills - such as the ability to recognise what information is relevant, to plan ahead, make decisions, to pay attention, remember details and stop us saying and doing the wrong things. Many of these skills are needed in making career decisions, aren’t they?

It is not that an 18-year-old can’t do these executive function skills. It’s just that they can’t control their impulsive limbic brain as easily or as often as someone with a mature adult brain who has had more practice and experience in using it!

When the pre-frontal cortex isn’t controlling our limbic brain, we see and hear the frequent outbursts, erratic behaviour and the risk taking that makes us fearful for all young people.

During adolescence young people may operate in their limbic brain 90% of the time. In fact, do you want to hear the limbic brain? Sit next to a group of young people at the sushi bar or on a bus. They talk quickly and get very loud and every third word is like.

Think of the brain as driving a car. In the teen years you are an inexperienced driver, your foot is hard on the accelerator and you apply the brakes infrequently and at the wrong time, which makes the driving experience erratic. But as you get older you become more skilled, so you know when to ease off the accelerator and apply the brakes smoothly and at the right time. The ride for everyone becomes more pleasurable!

In fact, there is strong evidence that female brains develop quicker than male brains because they emerge from puberty at an earlier age. So, it may be fair to say that adolescent girls on the whole are better drivers of their brains in these years.

So what should we do now we know more about the science of the young adolescent brain?

Firstly, we need to tell young people about this science. It won’t do any harm and in fact I have done that for the last 2 years and the look of relief on their face is amazing when they hear a valid and scientific reason as to why they feel confused and unsure.

And we all need to understand this science as parents, teachers and concerned adults. Maybe we will then be more patient with them, listen to them more and validate their thoughts and ideas. And not dismiss them too quickly just because they change their mind often or from one week to the next or it doesn’t make sense. They may be just trying an idea out to see how it ‘feels.’ It is part of how their brain is developing.